Interview with Fariddin Sharapov, Founder of Argo-Media, Uzbekistan.

In the heart of old Samarkand

— When and in what family were you born?

I was born on August 3, 1971, in Samarkand, right in the heart of the old city, opposite the Registan Square.

— How many children were in your family?

I had a younger brother, but unfortunately, he passed away at the age of 35.

A Spontaneous Journey Led to Choosing a Profession

— What did your parents do?

From Samarkand, my father went with a large group of friends to enroll in the Institute of Foreign Languages; it was a spontaneous decision. They studied at the Zhytomyr Pedagogical Institute in the Faculty of English. After graduation, everyone pursued their own professional path: some worked in Intourist, others at the airport.

— Why did your father choose Zhytomyr?

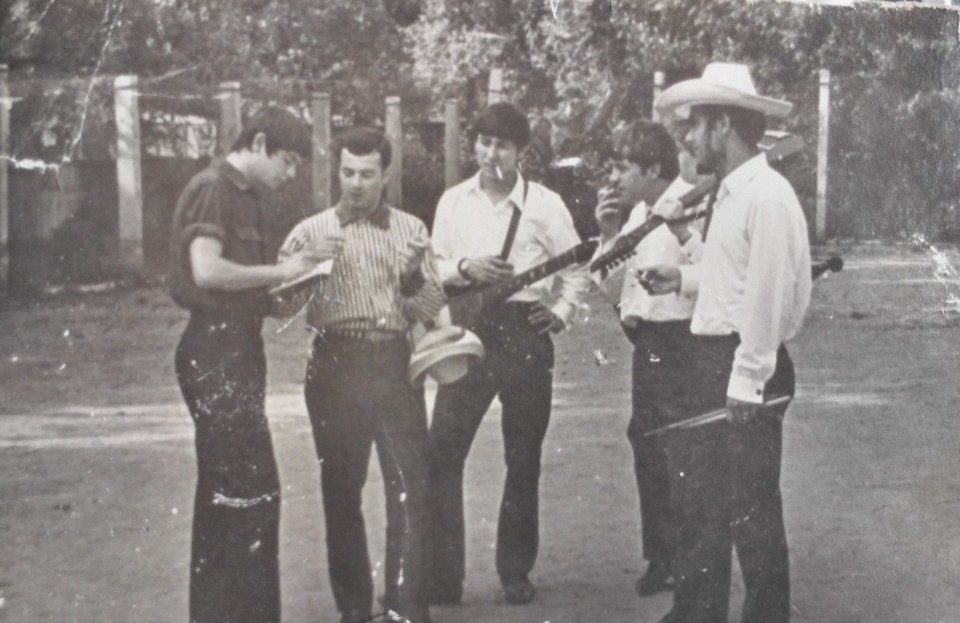

My father was an impulsive person and always went against the current. After a joyful evening at a restaurant, he and his friends saw an announcement about a traveling admissions committee from several universities across the Union while walking past the Registan. For some reason, they chose Zhytomyr as a group… At that time, my father was already interested in languages and played the guitar while his friends were drummers and bassists. The Beatles were popular then, which fueled his interest in English. His older brother also graduated from the Institute of Foreign Languages and worked in Intourist.

— Where did your parents meet?

My mother studied in the same place, in the French department. After serving in the army, my father started working in the internal affairs bodies. He worked in the traffic police of the Samarkand region as the head of the propaganda and agitation department, and later in the traffic police of Samarkand city. He served there until he retired.

My mother taught French in a school. It was a rarity in the old city.

— At what age did your parents get married?

They got married after finishing the institute. Then my father went to the army. There’s even a photo she sent to Siberia where I’m a little kid in a beret.

— Where did she live at that time?

In Malyn, with her parents. Initially, my father’s parents were against the marriage because Uzbekistan had different customs and it was difficult to adapt, but my mother quickly got used to the customs and learned the language.

— What nationality was your father?

My father was Tajik. He learned Uzbek when he started school. His father, my grandfather, deliberately sent him to an Uzbek class because they lived in Uzbekistan, and it was essential to know the language.

— Did he learn the language quickly?

My father was seated in the first row, and initially, he had a hard time because he understood almost nothing. But despite the difficulties, he learned both Uzbek and Russian languages.

Impulsiveness and Freedom: How My Father Chose His Path Against His Family’s Will

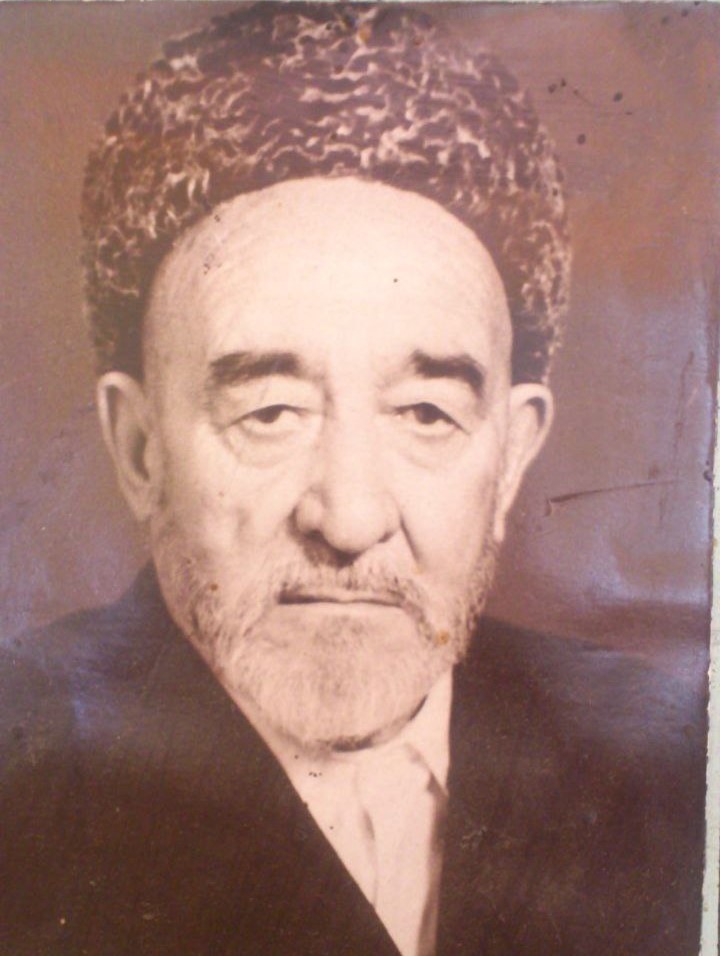

— What did your grandfather do?

Unfortunately, I remember very little about my paternal grandfather. He was what we would now call a businessman. Coming from a simple, poor family, as I was told, he managed to get a job with a wealthy man due to his hard work and curiosity. He quickly understood the complex process of managing an estate. Once, the owner sent him to Bukhara to sell a flock of sheep.

He sold the sheep, bought gold and jewelry with the proceeds, and brought them to Samarkand, asking the owner for a short deferment to sell the jewelry and repay the money. Thanks to his wit and business acumen, my grandfather soon became the manager and later married my grandmother, the daughter of that wealthy man.

— How did your father manage to go against his father’s will?

It was my father’s character. There were three brothers in the family. The eldest was sensible, calm, and always listened to their father. The youngest was very gentle, intelligent, and compliant by nature. But my father had a very tough character from an early age; no one could ever contradict him, whether he was right or wrong. When he decided to marry my mother, he knew his family would react negatively. But everything had to be just as he decided!

— Was there resistance from your mother’s relatives?

Credit goes to both my mother and her parents. They not only managed to smooth over all the rough edges but also created a strong, international family. Soon, all the problems faded away.

There was a loud and beautiful Ukrainian wedding where my father wore an embroidered Ukrainian shirt; a colorful and vibrant Samarkand wedding where my mother dressed as an eastern princess in an Uzbek bridal outfit; and a civil registry office ceremony with a white wedding dress and my father’s parade uniform. Everyone was satisfied!

Polyglot and Music Lover: How Knowing Foreign Languages Helped My Father in Work and Life

— Did the foreign language help your father in his work?

It helped a lot. He was probably one of the few employees of the Samarkand Department of Internal Affairs who knew several foreign languages. In addition to American and British English, which he knew perfectly, he was fluent in Uzbek, Tajik, Ukrainian, Russian, German, Persian, and could also communicate in French…

He and my mother often sang English, French, and Ukrainian songs together. During his studies in Zhytomyr, he and his friends formed a vocal-instrumental ensemble called “The Pickles.” Language was his strong suit.

— Did he often have to meet with colleagues from abroad for work?

Once, during a family trip to the mountains, we encountered a broken-down tourist bus. The passengers were trying to explain something in English to a young traffic police inspector. The tourists were amazed when my father approached them and started speaking their native language! The group turned out to be New York police officers touring Central Asia by bus. The bus was quickly repaired, and my father was left with a souvenir set from the New York police: handcuffs, a whistle, and other items. I proudly showed them to my friends later!

Of course, besides such pleasant situations, there were also very serious cases where he had to communicate with colleagues from Interpol and other international organizations.

— Did your father start working in the internal affairs bodies right after the institute?

Here’s a little background. After graduation, my father returned to his native Samarkand and began working in a school, first teaching English, then becoming the deputy principal. During a cotton-picking trip, he received news that a serious commission from Moscow was coming, and it was necessary to meet the commission and show an exemplary cotton-picking process. My father, then the deputy principal, waited all day for the group, which arrived late at night in a very high spirit. The commission included a member of the city party committee who was my father’s classmate and neighbor. Instead of greeting him normally, this person started acting like a big boss, complaining that the children were not picking cotton and that my father, as the deputy principal and the group leader, did not ensure the exemplary cotton-picking process by the bus headlights…

Using foul language, this party official got a broken jaw, and my father was sent to serve in the internal troops in the taiga.

– Did the family try to help him?

My mother tried to get him out. She asked my great-uncle, who worked in the USSR Ministry of Forestry, for help. Miraculously, my father was sent to serve the rest of his term in the construction battalion in Samarkand.

— How long did he serve?

He served relatively briefly. He managed to stand out even there. In the unit my father commanded, soldiers wore the so-called “Afghan uniform,” with an open-collar shirt, a panama hat, and American-style boots instead of standard-issue boots.

– Yes… when it’s +45 to +47 degrees outside in summer, +50 to +60 on the parade ground, you can’t manage otherwise…

Once, during an inspection from the capital, a strict general arrived who found the standard procedures of painting grass and catching falling leaves insufficient. Gathering the officers, the general expressed his deep dissatisfaction with the soldiers not being in regulation uniforms. My father dared to argue with him, and after a short but intense verbal exchange, the general promised to transfer my father to Kushka. Not waiting to be sent to the “warm region,” my father called my grandfather in Moscow, and by the time he returned from the phone station, the general received a return call. The general decided to prove his point by example and went to the parade ground to march in full dress. The result was heatstroke and a heart attack.

– Your father had a heightened sense of justice.

Yes, he was extremely responsible. Such people were highly respected back then. Paradoxically, the internal affairs bodies were a separate world where people served not for privileges. An officer’s honor was above all. The entire officer corps had to have a specialized higher education. During his service, my father completed a law degree by correspondence and graduated with honors from the Higher School of Militia.

– Did any repercussions follow the incident with the general?

After that incident, my father was given a choice: either fully face the consequences of his “misconduct,” with all that entailed, or join the internal affairs structure. So he started serving in the internal affairs bodies.

Favorite Subjects and Challenges in Education

— How did you do in school? What subjects did you like?

I wouldn’t say I did super well. I was often sick and missed school. My first grades were not great. My favorite subjects were probably history, literature, and physics…

In college, I came to appreciate and love the beauty of mathematics. I realized it is indeed a great science, the queen of all sciences. Chemistry was also a very interesting field.

— Did you finish school well?

Yes, I didn’t have any Cs, only Bs and As. I finished school well, although I actually changed schools twice.

Youth Hobbies

— How was your life outside of school? Did you attend any clubs?

My hobbies were photography, radio, and then playing the guitar. But mostly radio, photography. Initially, black and white, then color. It was almost at a manic level. My parents put up with it. Our bathroom was constantly occupied — there was a tabletop from a coffee table across the bathtub with a photo enlarger, trays with solutions, jars of chemicals, and the veranda was full of radio components, receivers, antennas. It was my mother’s nightmare come true.

— How did these hobbies come into your life?

Probably from my father, although he wasn’t very into photography, he was more of an amateur. Love for singing — that’s both my father’s and mother’s genetics, both families had excellent voices and hearing.

— And where did the interest in radio come from?

I don’t know where radio came from… I always felt like I was born with a soldering iron in my hand. My mentor, the head of the radio club at the House of Pioneers, Gaisyn Gennady Mansurovich, helped develop my interest. I was always interested in taking things apart to see what was inside and how they worked.

– Were your parents strict?

I hardly remember my father outside of work. He often traveled, he had a “go-bag.” My father would take it and disappear for a month or two because times were turbulent. My mother taught, and we saw each other only in the evening.

When we were little, there was a tradition in the traffic police where my father worked to go to the mountains with families at least once every two weeks. These were wonderful picnics, with three or four buses gathering. It’s one of my most vivid childhood memories. And three months of summer vacations in Malyn, near Kyiv, Zhytomyr region, where my maternal grandparents lived.

Living in Two Cities

— You mentioned living in two cities…

Until the fourth grade, I studied in Samarkand. Then my mother was hospitalized in Zhytomyr after an accident with my father. She needed constant check-ups, and there was a good clinic there. My mother traveled there frequently, and I moved to live with her and studied in Malyn for a while. Then I returned to Samarkand.

— Is Malyn a Russian-speaking city?

A dialect called Surzhyk, a mix of Russian and Ukrainian, was commonly spoken. In summer, many children from all over the Union came for holidays. No one bothered about the language. My brother and I didn’t differentiate between Russian and Ukrainian. In Zhytomyr, Kyiv, Kharkiv, industry was well developed, and many people moved there. Kharkiv was more Russian-speaking, while Kyiv and Zhytomyr were more Ukrainian-speaking.

Malyn, where I lived, was also multinational. There were Georgians, Uzbeks, Russians, Jews, Poles. A typical Soviet Union mix. Everywhere.

In Samarkand, there were more than a hundred nationalities. Many people settled there before and after the war. Repressed individuals, Japanese prisoners, Crimean Tatars, Meskhetian Turks, Germans, Koreans, Ukrainians, Poles, Armenians, Azerbaijanis — you name it.

How an Internship at a Factory Defined My Career Choice and Future Career

— After school, did you decide on your own where to go or did you decide with your family?

I had severe asthma, and doctors recommended changing the climate — somewhere humid and less dusty. I decided to follow my father’s example, took a map, marked several cities, closed my eyes, and pointed at Moscow. At that time, there was a significant difference between the school programs in Moscow and Samarkand, so I attended clubs and preparatory courses for admission to Moscow universities. Especially in physics and mathematics. I definitely wanted to enter a technical university, and luckily, the Kinap factory, where I interned, sent applicants to one of the Moscow institutes — Stankin.

— What specialty did you choose?

Instrumental systems of automated production.

— Why that particular specialty?

I’m not sure why, but it was a faculty where, in addition to the main subjects, they also studied programming. There were CNC (computer numerical control) machines. At that time, there was a Soviet development called TopCAD — the first CAD system that worked on ES series computers. By the way, we created a CAD system for the Moscow Ilyich Plant on it. During the internship, we even implemented some modules into production.

Professional Skills

— Looking back, how do you think your education benefited you?

Everything. Really everything. As a specialist and professional, I was shaped by my teachers. Whomever we approached, on any department, course, or elective, they always said the same thing: You came not to study a subject, but to learn how to learn. The ability to adapt, systematically approach finding and assimilating information allowed me to later master many different professions.

– Which ones?

These skills, starting from the main subjects taught by our professional teachers to electives on ancient Indian psychology, gave me much in terms of discipline and life principles.

The method of studying material used by the teachers helped me find myself, as I worked in many fields. They are interconnected. It’s all related to mass media, but the range is huge: from TV technician to general, commercial, and financial director positions, and so on. Different fields: printing, publishing, radio, television, and now technical event support.

From TV Technician to Professional: How Studies and Principles Helped in Life and Career

— You mentioned you started as a TV technician. Was it during your studies or after?

It was in childhood. The first time a neighbor asked me to check his TV. Something wasn’t working. I was about 10. I went with my soldering iron and tester, checked it, found the fault, and fixed the tube TV. The neighbor gave me three rubles. I proudly showed them to my father, but he scolded me harshly and made me return the money.

– Why?

He said never to take money from friends, relatives, or neighbors. That was a life lesson. At that time, it was a shock to me, thinking I earned it honestly, but couldn’t take the money. But later, I understood. Money is one thing, relationships are another. They should never be mixed. There are principles, and you must stick to them.

All the knowledge and skills acquired in the institute helped me become who I am and achieve what I have. And I have done quite a lot.

— Did you work during your studies?

Like all students, I worked at the vegetable base, unloading trucks. It was fun when a crowd of people gathered and in the December frost went beyond Moscow on Leningrad Highway to unload contraband Polish liquor. Then we walked to the nearest train, sipping the liquor to stay warm. It was frightening, of course. The main thing was it was hard to warm up afterward. Since then, I don’t drink liquor. Actually, I don’t drink at all.

Graduating from the Institute

— When you graduated, did you have to return?

When I graduated, unfortunately, there was a severe loss. On March 21, 1994. I was celebrating my diploma defense at my aunt’s house in Moscow. In Uzbekistan, it’s a holiday, but I got a call saying my grandfather passed away, and my parents couldn’t go to the funeral because it was a holiday, everything was closed, money was different then.

— Was your grandfather close to you?

I grew up in his arms… Friends gathered money and somehow put me on a train, crying. Early morning, I was in Malyn. My parents managed to come. My father, as an internal affairs officer, had a free flight opportunity once. After the funeral, my parents insisted I return to Samarkand. I think my father was very afraid I’d stay in Moscow, marry, and follow his path.

— Why was he afraid?

People change with age. He felt he did right, all was well, but the son should find a “proper” wife from a good, wealthy family. Though he was never like that himself. There were attempts to matchmake and marry me. Nothing came of it. But they took me from Moscow.

— What did you do when you returned to Samarkand?

I returned and didn’t know what to do. The factory that sent me to the university had almost collapsed. The director released me from mandatory work. I worked in accounting since I knew computers and programming, anything related to math and programming was easy and fun. I also fixed and set up things on the side.

Starting a Career in Television: How a Chance Led to a New Profession

— Did you join television at that time?

By chance, I ended up at a private Samarkand TV station. The channel’s director was my relative, my cousin’s husband, Firdavs Abdukhaliqov. In 1989, still under the Soviet Union, he opened a private youth channel. Back then, no one even thought television could be private. It was a maniacal, in a good way, idea, and he realized it.

— What year was it?

I joined in 1994. A great team, young guys, all creative, all with crazy genius ideas, wanting to do something new for Samarkand and Uzbekistan, with ambitions in a good sense. I joined casually, TV was TV, I was practically a TV technician, roughly speaking.

– What were your first impressions?

After settling in, I started seeing how things worked, where there were issues, and what could be fixed. The Stankin spirit of perfectionism was indignant at first. Seeing cables twisted together or open video recorder tops for quick “technical service” made me feel sick. I fixed things, did things from scratch.

I greatly benefited from communication with the Samarkand Radio and Television Transmitting Center (RTPC) staff, where our broadcast control room was located. I warmly remember all the staff, especially the RTPC chief, Mark Borisovich Feldkoren, who became my teacher and close friend.

— What was your first position there?

I came not knowing what. My good friend Ravshan managed the TV station. He called me “engineer” from the first days. The nickname stuck quickly and for a long time… Even when I became the general director.

Technical Equipment

— How was television then?

At that time, the first private cable studios were just appearing. In apartment buildings, there were video recorders — at best Hitachi, at worst “Electronics VM-12.” Distributors called “crabs,” twisted cables, and this “network” broadcasted. Some had better signals, others worse. The television was about the same level, but the transmitters and antennas were professional.

On the Samarkand telephone exchange building was our RTPC Samarkand’s control room, monitoring all channels. Two or three state channels, one local, two national channels. They monitored them, and we as privateers broadcasted from there.

– What equipment did you use?

A large buttoned-up SKM panel, two video recorders, a “titler” assembled by the “Okno TV” wizards (then a small Moscow firm) from an Atari computer and their DAC.

Technically it was scary. No one knew or heard of synchronization, the transmitters were analog, but you understand how they work with unstable signals — stripes appeared on the air.

I Soldered a Circuit and Made a Seamless Switcher. It Was a Real Breakthrough

Then I soldered a circuit and made a seamless switcher, which switched several camera and video signals during the blanking interval. It was a real breakthrough: we could say we were ready for live broadcasting, we had a “mixer.” That’s how it all started.

Company Growth

— How long did you work at that channel?

Considering the television itself, probably until 1999. In 1998, we opened a radio station. At the same time, we organized a newspaper editorial office and publishing house, “raised” the regional printing house, modernizing it.

— In one position?

At that moment, I transitioned from technical director to general director. Then gradually, since the editorial office moved to Tashkent, we started commuting between Tashkent and Samarkand, sometimes twice a day.

From around 2001-2002, I fully moved to Tashkent. We started a project to create the “Poytakht” (“Capital”) information radio station in Tashkent then.

— Did you leave the company or continue as director?

The company grew, with two major projects in Tashkent — a newspaper editorial office and a radio station. The radio station project began with our Samarkand team. There were 13 of us. We stayed in two rented apartments, one numbered 13, and took tram 13…

National Association of Electronic Mass Media of Uzbekistan

— When did the association idea arise?

Along with the radio station, a new huge project began in 2003 — the National Association of Electronic Mass Media of Uzbekistan (NAESMI).

— What is it?

This project still exists, uniting over 100 non-state media, TV stations, radio stations, cable TV studios, electronic media.

– When did you join the project?

I went “freelance” in 2017, deciding to start my own business. Many of our friends jokingly say I’m the oldest employee who managed to work with our dear Firdavs Fridunovich for over 20 years straight. The reason is his difficult character and extremely high standards. However, his school is a real survival school. He taught me a lot; he’s a creative person with a genius sense, who did so much for the media sphere of Uzbekistan and beyond that it’s hard to overestimate.

— Who created NAESMI?

The founder and ideological inspirer of almost all our projects, Firdavs Fridunovich Abdukhaliqov. From 2003 to 2019, he headed NAESMI. Then he became the chairman of the national “Uzbekkino” agency and recently headed the Center for Islamic Civilization under the Cabinet of Ministers of Uzbekistan. This role continues another of his major international projects — the “World Society for the Study, Preservation, and Popularization of the Cultural Heritage of Uzbekistan,” founded and led by him for many years.

— Who else participated in creating NAESMI?

In the distant 1994-95, we attempted to create a broadcaster association. We received great support from another famous Samarkand native — Eduard Sagalaev. He granted us exclusive rights to retransmit the TV-6 channel across Uzbekistan. If you remember their branding — there were images of New York, Moscow, and Samarkand. No Tashkent.

— How did you start?

The structure was initially called ANESMI (Association of Non-State Electronic Media). We were the first in Uzbekistan to buy the rights to the Brazilian series “Black Pearl,” if I’m not mistaken. We signed contracts with regional non-state TV studios for TV-6 retransmission, and in the regional “windows,” stations broadcasted our content (the series, original programs) as well as local and centralized ads.

— How many regional non-state TV studios were there then?

It was the first serious attempt to move away from “piracy” and build a harmonious regional network broadcasting system, simultaneously solving the regional studios’ issue of access to licensed content.

During this period, we closely acquainted with all regional stations. There were over 30. For example, in Bukhara, there were three non-state stations, in Navoi two, in Samarkand two, in Tashkent two or three.

— Where did you get the content?

The uniqueness of the Uzbek regional TV model was that initially, the broadcasting schedule was based on local news. This was the appeal and advantage over national channels. Naturally, the schedule included concerts, greetings, movies, especially Indian ones (our audience cried if there wasn’t an Indian movie on Saturdays), but local news and talk shows were always flagship content.

The uniqueness of the Uzbek regional TV model was based on local news

— How did the authorities react to this?

The media is rightly called the “Fourth Estate.” The country’s and regions’ leadership mostly positively related to journalists and respected them. There were, of course, exceptions…

Development of Media Projects: How the Move to Tashkent Affected the Company’s Activities

— When you moved the company to Tashkent, what changed?

The STV TV and Radio Company never moved and continued to work in Samarkand. Part of the projects moved to Tashkent.

So it’s more about expansion than moving. In the capital, there’s wider access to information, more commercial opportunities. Initially, there was a metropolitan branch office for the newspaper, as interviews with celebrities were needed, exclusive photo materials prepared, and filming for television done.

— What happened next?

Later, other larger projects were organized, as mentioned, the “Poytakht” radio station (two waves in Russian and Uzbek), the National Association of Electronic Media, the Public Fund for the Support and Development of Non-State Electronic Media, the Uzbekistan Today news agency, the NTT television network, and many other projects.

Activities of the Association

— What was your position in the association?

At different times, I was the technical director, general producer, executive, and general director of projects. Often, I led up to five structures simultaneously, including NAESMI, the Public Fund for the Support and Development of Non-State Electronic Media, the NTT television network, the Uzbekistan Today news agency, and a couple of smaller projects.

— What did the association do?

The association actively interacted through its projects with many state, foreign, and international organizations, attracting grants aimed at stimulating the development of Uzbekistan’s electronic media, organizing various festivals and contests regularly.

— What events did you hold?

We provided regional media with equipment, brought in trainers for journalists, operators, and producers, organized training summer camps and field events. It was extensive work. We held 3-4 major festivals, many contests, grant projects, seminars, and training sessions annually.

— Did NAESMI help in the transition to digital?

NAESMI actively participated in the process of transitioning to digital broadcasting. By 2008, Uzbekistan was one of the first in the CIS to complete the transition from analog to digital.

Transition to Freelance

— What happened in 2017? Why did you leave?

Currently, there are 15 state channels and about two dozen non-state ones in Uzbekistan, including five major federal channels with good ratings. This is the result of meticulous work over many years.

Working in such conditions is constant stress. Sometimes, I had to manage several projects simultaneously, 24/7 without weekends, and around the clock during holidays.

— It’s easy to burn out in such a regime…

At some point, I realized I needed to spend more time with family, achieve financial independence, and start working for myself!

— What did you do?

In 2017, I opened a small firm with two employees. We did what I loved — technical consulting and maintenance. The work was diverse: from preparing documents for registering a TV or radio station, consulting on administrative and commercial issues, to solving tasks on modernizing TV and radio studios’ equipment, creating multimedia projects. Later, closer to 2018-2019, we began holding conferences and teleconferences, including at the state level.

In 2017, I opened a small firm for technical consulting and maintenance

— What conferences?

I was probably one of the first “privateers” to do this. Usually, for teleconferences and live broadcasts, the standard scheme of OB vans (outside broadcast vans), mobile satellite receiving and transmitting systems, plus ground relays through radio relay equipment were used. In some cases, there were huge delays due to digital device buffering, multiple segments, etc. Available VCS systems had much less delay but were unacceptable quality for broadcasting. So, I began experimenting with different codecs and implementing IP relays with minimal delays and adequate quality.

Fortunately, by then, Uzbekistan had an extensive optical communication network, thanks to the national operator “Uztelecom,” with whom I’ve collaborated for many years. The success of many NAESMI projects, especially the NTT television network uniting all non-state stations, largely depended on the specialists’ and managers’ work and understanding at this wonderful organization.

Teleconferences and hybrid events were a breakthrough in business development

Teleconferences and hybrid events were the first significant business breakthrough. They brought in the first substantial finances, immediately reinvested in equipment and personnel.

Pandemic

— How did the company develop further?

Paradoxically, the pandemic was another significant boost. It was a time for a reset. I realized the world was changing, and new realities were emerging, which had to be either embraced or left behind.

— How did the pandemic affect your business?

Until 2019, our company mainly handled large events, developing technical concepts, synchronizing light, sound, LED screens, video shooting, and only occasionally video relays and teleconferences. The hybrid event format was not in demand. Remote users were mostly Japanese or Americans. Other foreign guests preferred to fly to Tashkent, Samarkand, or Bukhara and enjoy a good pilaf and kebab rather than connect online, fending off their cat.

— Did you transition to new communication formats?

It often required more than just Zoom meetings, like proper teleconferences for doctors. Remote consultations and assistance during complex surgeries were often needed. Telemedicine was just starting, and we tried to keep up. My event work expanded to various teleconferences, streams, etc.

Broadcasting

— What areas does the company cover now?

The company continues to work in technical broadcasting support. About 12 TV stations actively communicate with me and are under my service.

12 TV stations actively communicate with me and are under my service

We work with software and hardware manufacturers for broadcasting automation. One of my oldest and most reliable partners is the Novosibirsk-based “Softlab” company and personally Mikhail Shadrin. Their automation systems operate in most private and some state TV channels.

One of my oldest and most reliable partners is Novosibirsk’s “Softlab” and personally Mikhail Shadrin

— Do you serve them as system integrators?

Yes, I have technical specialists in Tashkent and regions, a team, and most importantly, expertise. Sometimes, a client comes and says: “I want to open a TV station.” Their idea of a TV station is a couple of computers and cameras. We have to explain that television is a complex system, including many components, from ventilation and wiring to cameras, processing, keyers, augmented reality systems. Plus, documentation, personnel, commercial aspects, and so on. It’s crucial to help the client understand what they want. Then it’s easier. We prepare the TOR, agree on the financial part, and go ahead!

— Do you collaborate with old TV channels?

Existing TV channels’ requests also change. More frequently, they request teleconferences and live broadcasts. We try to provide our services in this field. The market is very competitive, but due to various circumstances, standard solutions are not always convenient or functional. We try to find the best approach for each client. We actively use cloud technologies, deploy dedicated servers for clients, rent out ours — all for the people!

We actively use cloud technologies

— Do you just rent equipment?

We have our equipment fleet. Mainly for technical event support. Shooting equipment, media servers, congress systems, simultaneous translation systems, PTZ camera auto-guidance systems, multichannel audio and video recording equipment, streaming equipment, etc. We often act as general contractors, developing the overall technical concept of an event and engaging subcontractors, catering, decorators, etc.

— What do you consider your main career and life achievement?

My family and close ones, they are still with me, I have them, and they live in normal conditions. The main achievement is being part of Uzbekistan’s media sphere.

The main achievement is being part of Uzbekistan’s media sphere

I consider myself involved in everything happening now, both directly and through my students. It’s nice to realize I was at the origins of independent broadcasting in Uzbekistan. I sincerely take pride in all the projects I participated in creating and implementing.

Personal Life and Family: A Success Story Beyond Work

— How did your life outside of work unfold? Were you matchmade?

Absolutely not, all attempts were in vain. I chose my fate myself. When I worked in television, in 1995, a young girl joined us, studying physics at Samarkand State University. Usually, all technicians and programmers were sent to me. But she was intercepted by our advertising studio.

She was very photogenic, quickly got used to being on camera, and knew both Russian and Uzbek. So, she became a commercial program host. But she was interested in computers and 3D graphics, which was my domain, so a meeting was inevitable. We started dating and married in 1996.

— Do you have children?

In 1997, our son was born. Three years later, a daughter was born. While the kids were small, I worked a lot and wasn’t always home. Someone had to watch them. When they grew older, she gave me an ultimatum, saying she wanted to work.

— Does your wife work now?

She joined an advertising agency with about ten employees, the largest in Tashkent for print media. Over time, some employees went on maternity leave, some quit, and she took over the entire agency’s work. This lasted until the pandemic. The print media market gradually declined, and when she began using family money to support the agency, I told her it was time to change jobs. Now she works at my firm. I’m the founder, she’s a co-founder and director. She actively participates in all our events.

— How have your children fared?

Our son, Jonibek, often called Jonik, graduated from Westminster University in Tashkent. Like his grandfather, he easily learns languages. He speaks English and German. He worked in several companies and now works in a large advertising agency. He is exploring different fields and is also a musician, a drummer.

Our daughter, Sitora, also known as Sita, is an artist, teaching a bit, and working as a designer. Recently, her company received a significant order, and her illustrations adorn new textbooks for primary schools in Uzbekistan.

I eagerly await when they find their soulmates!