Interview with David Wood, Consultant, Technology and Innovation at European Broadcasting Union.

Who were your parents, and where and when were you born?

I was born in Wales in the UK. My father was an engineer and aircraft designer for several companies, such as Miles Aircraft in the UK. I was born in Newport in South Wales. I grew up in the Welsh Valleys, and I went to university in the UK. I studied electronic engineering at the University of Southampton, which was quite famous for its electronics courses in those days.

Why did you choose Southampton University?

This was in the 1960s. In those days, there were only a few universities in the UK that studied electronics. One of them was Southampton. The University of Southampton had a great reputation, and I was lucky enough to be accepted there. When I left university, I went to work for the BBC Research Department.

Did you get accepted based on a scholarship?

In the UK you had to sit exams called ‘Advanced Levels’. The university you wanted to go to interviewed you and accepted you if you attained certain grades on your exams. I was fortunate enough to get those grades and so could go to the university of my choice.

What subjects did you like in school?

My favorite subjects were Physics and Mathematics, but I was also very interested in Music. I played in some bands when I was in school. This led me to like the combination of electronics and entertainment. When I was a child, I always had a dream to work in broadcasting. I wanted to either be an electronics engineer or an entertainer. I can tell you, it is much easier being an electronics engineer.

Were you a good student?

I am not so sure. When I was in school, I was in a band and we used to do concerts — rock and roll, folk music, and so on. I suppose I also spent a lot of time in university and afterward playing in bands as well. I managed to get through it, and I graduated. I was interviewed by the BBC, and they invited me to join their Research Department when I left university.

Where did you get your Ph.D.?

Among the other work that I did, I worked on something which may seem esoteric: the way you evaluate color television picture quality. I helped to develop a CCIR/ITU Recommendation (Recommendation 500), which is still the basis for the way television pictures are evaluated. The public at large are not experts, so we take assessors who are not experts and ask them to grade television picture quality in a scientifically controlled way. In this work at the CCIR, I was honored to meet a gentleman who was a Professor at the Popov Institute in Odessa, in Ukraine — Oleg Gofaizen. Few in those days thought the subject of the quality evaluation was important, but he did. He asked me if I wanted to come to Odessa and do a doctorate in quality evaluation in his department. So, I got my Ph.D. from the Popov Institute in Odessa. Unfortunately, last Christmas both Oleg and his wife died of COVID-19. I will always remember them and the time I spent in Odessa. He is one of my heroes.

When did you come to the BBC?

I joined the Research Department of the BBC in 1968 and was there for several years. I began with work on the development of antennas for satellite broadcasting in the home. I also worked on the development of a system to allow color television cameras to be lined up using ‘skin tones’ — these are the types of colors humans have the most acuity to. I worked for the BBC for about five years, then I moved to the other side of UK television: the Independent Broadcasting Authority. When I left the BBC, I was a senior engineer there.

Why did you leave the BBC?

I love the BBC, and I have always worked with them a lot. The truth is, I was then working in the center of London. London is such a terribly busy place, it was full of people, cars, and noise. As someone who came from the country, I really wanted to move out of London. My home was in Wales, and I used to have to get up at three in the morning just to drive down to Wales because the traffic getting through London was so bad! I left the BBC not because I did not like it, but because I really wanted to get out into the country again. The Independent Broadcasting Authority center where I worked after that is out in the country, in a place called Winchester. This is also near Southampton — this is a town I love because it was where I went to university.

What was your position at the Independent Broadcasting Authority?

I was an engineer and writer. My work there included Teletext. This was a system used in Western European countries; I suppose it was a sort of forerunner to the Web. Data signals can be translated into pictures and text on the screen. When I joined the IBA, my colleagues had developed this, and I was asked to edit and manage the world’s first demonstration Teletext magazine. I was trying to assess what the public would want from such a magazine. I did some market research and I learned a lesson: if you just ask people that have never seen a new technology what they would like, they do not know. People must see and try the technology themselves before they know whether they want it.

What did you do after the Independent Broadcasting Authority?

To be honest, my career, insofar as it was involved with things that shaped broadcasting, really began when I left the Independent Broadcasting Authority in 1979. I saw an internal advertisement and joined the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). It is a kind of ‘club’ of national broadcasters. Its history goes back to 1922 as the OIR. It later had a Western European child, the EBU, and a child which included the Central and Eastern European countries called the OIRT. The chance to join the EBU in Brussels was really exciting.

How did you apply?

I applied for an attachment to the European Broadcasting Union for two years. I had some interviews, they asked me a lot of questions about digital television which I was, fortunately, able to answer. Then, my family and I moved to Brussels, and I worked at the EBU Technical Center. They asked me to help coordinate the research and development that was being done by European broadcasters in digital television. This was a great opportunity because I got to meet, discuss, and work with the major broadcast research and development laboratories across Europe.

Was it an international team?

That is right. The staff of the European Broadcasting Union’s Technical Center in Brussels comes from all over the EBU member countries, on attachment from France, Germany, Italy, and so on. My area was digital television and the development of its standards for common use throughout Europe. This was how I got my first ‘break’ into doing something which some see as helping to change the media world.

How did you set up these standards?

Up until that time, a television in Europe had used different analogue standards. My job when I first arrived was to try to work towards a single common digital standard. Our first objective was a standard that could be used for programme production. However naïve it was, we thought we could make one that could serve the whole world. We tried to find the values of digital parameters that would make it usable across the world. After many tests, we devised a set of parameters with just one difference in different parts of the world — the frame frequency. We were able to work with and persuade the SMPTE in the US. Together, we arrived at this set of parameters, which is often called the 4:2:2 format.

How did you work with other groups and countries on this issue?

I tried to take it to other parts of the world and convince them that these were a good set of parameters. One of the first stops I made was to the OIRT: the Eastern and Central European collective organization of broadcasters. I went to a meeting in Hungary and met with the super helpful Rozcena Jezkhova and J.M. Krylov. By the end of the meeting, we had a West and Eastern European agreement on this common set of parameters for digital television. We then took it to the International Telecommunications Union (CCIR/ITU) to try to make it a worldwide standard in 1982. I met a great friend and colleague there — Mark Krivosheev. At that time, he was the chairman of the CCIR. We got the whole world to agree to this! It was then called Recommendation 601. That recommendation is really the basis from which all digital television flows.

How did you continue to work on this?

Then, internally in the EBU, we moved to look at the issue of how we could broadcast programs made with Recommendation 601. At that time, we thought that having a unique standard was something of a lost cause — we could not succeed in changing the broadcast systems PAL and SECAM. This led to the development of a new analog television system called the MAC (Multiplexed Analogue Components). It must be said, events overtook us, and it was not many years before it was clear that the better option would be to have a digital broadcasting format. The MAC story was interesting but not a success, I would have to admit.

Can you talk about the development of high-definition television during this time?

While this was happening, in the 1970s, there had been work in Japan on high-definition television. The idea for this came during the Olympic Games in 1964. They thought there could be a new television system that was twice as good so that the public could really enjoy the presence of events such as the Olympic Games. In the EBU, we too wondered whether we could develop a high-definition television standard built on Recommendation 601. There were several proposals for doing so — one developed in Japan and supported by the US. Another emerged from an industrial consortium in Europe, the HD-MAC Project.

How did you develop this?

This was one of the most exciting times for me. Among other steps, thanks to Henrikas Yushkavitshus and George Waters, we set up the ‘Moscow Group’ together with Valery Khleborodov and his team at Gostelradios’s VNIITR. We arranged tests to judge the extent to which viewers would see the difference between reality and high-definition television. This involved showing people real objects, and then those same objects on high-definition television.

Was there a lot of disagreement between different groups and countries?

In the middle of the 1980s, there had been a CCIR (now ITU) meeting in Dubrovnik, in Yugoslavia. There were a lot of enmities there between the Americans and the others about what the principal numbers for HDTV should be. The Americans insisted on 60 frames a second because that is what they use. Others, including those in Europe, thought that it should be 50 for the same reason. There was no agreement reached on the HDTV format used for some years. We did eventually agree on a system, which used a so-called ‘Common Image Format’. This allowed you to have a frame-rate switchable arrangement with the rest common.

Did you work on anything else noteworthy during this time?

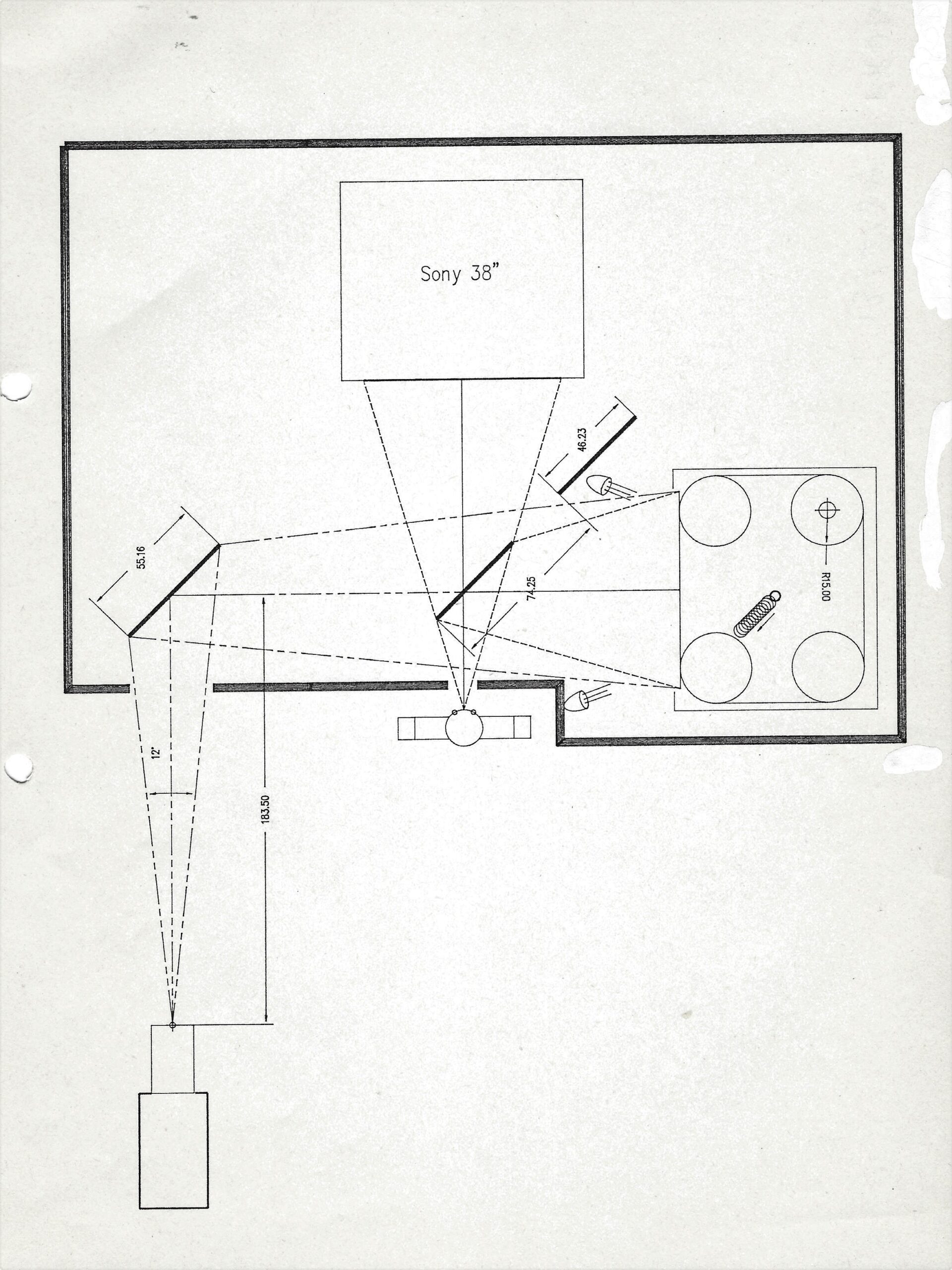

I then worked on another project in Europe. The EBU Technical Committee, together with those in the industry group PALPlus, realized that we could have a common delivery format if we went digital. We established the DVB project in the early 90s, thanks to the efforts of many. We first looked at digital satellite broadcasting. The trick was in the compression technology. At that time, using the normal type of compression technology (DPCM) would have meant bandwidths that were well more than those available for satellite television and terrestrial broadcasting. It seemed impossible to reduce the bit rate of a digital television signal, even a conventional quality one, below 34 Megabits. Then, work was done on a new type of compression format called DCT (the Discrete Cosine Transform). This would lead to dramatically lower bit rates available from compression. The magic seemed to be that we could reduce the bit rate to something practical for satellite, terrestrial, and cable networks if we developed broadcasting or delivery standards using DCT. The first one we tackled was DVB-S — a system for satellite broadcasting.

Did you only do this for satellite broadcasting?

We then turned to digital terrestrial broadcasting. This was a more complicated environment. The US had been working on their own digital standard — ATSC. Thus, it seemed that they would be unlikely to agree to accept another standard. We tried to find one that would draw on the work done on ATSC, but using later developed tools. We developed a couple of standards over the years, DVB-T and DVB-T2. Personally, I still think DVB-T2 is probably technically the best terrestrial standard in widespread use today.

Where did you work after this?

In about 2008, I was asked by Christoph Dosch, the Chair of ITU-R SG6, to come back to the ITU. I suppose I may have had something of a reputation for being good at finding compromises between different groups. The work I did in the ITU-R was successful, one of the reasons was because I learned from Mark Krivosheev. He had two frequently made points of philosophy, which I always applied. The first was to always take a global approach and find a win-win situation for the whole world. The other is to keep your eye on the results you want to achieve and not get bogged down in the process and the rules.

Had you lived in Brussels this entire time, for 20 years?

After ten years the EBU moved from Brussels to Geneva, in Switzerland. I quite liked Brussels, actually. But at least in Switzerland, they speak French much slower.

What was your position when you came back to the ITU?

I was chairman of the Working Party 6C. I really loved meeting people from other parts of the world and trying to understand how they saw things. I thought that if I had a talent, it was being able to see things from other people’s viewpoints. You only really get that if you talk to people and meet them regularly.

What was your goal when you returned to this chairman position?

A main goal of 6C was to agree on a common worldwide standard for UHDTV (ultra-high-definition television). I tried to understand what the technically good parameter values were. The UHDTV discussion was not, as it had been, between Europe and the US. The debate was essentially between the views of Korea and Japan. They both had major interests in UHDTV, whereas Europe was only just coming to terms with HD. I tried to understand the Japanese and Korean perspectives.

Were you successful in this goal?

We worked on this for several years and in 2012 managed to arrive at a common Recommendation. It became the worldwide recommendation for ultra-high-definition: ITU-R Recommendation 2020. This was the third ITU recommendation in this series (601, 709, and 2020) for which I had been lucky enough to be a principal. We are still waiting for UHDTV to be a great success, but it is slowly moving forward.

Why do you think the move to ultra-high-definition television is so slow?

4K UHDTV, or UHDTV-1, is something of an improvement on HD television, but it is not the same gap as between standard definition and high definition. The original idea for UHDTV was one system, the so-called ‘8K’. We thought initially that the jump between high-definition and 8K would be about the same as the quality jump between standard definition and high definition. Unfortunately, the TV set makers explained that they could not make, at that time, 8K television sets. They wanted the public to move in two steps: high definition, to 4K and then to 8K. The difference between high definition and 4K is not as dramatic. Making the jump is arguably a harder sell to the public and the content providers.

Do you think we will reach this eventually?

If you look at what has happened – NTSC, PAL, SECAM, 601, 709, 2020… — there is only one way that quality goes: up. In the end, whether it is 20 or 30 years from now, we will have full UHDTV. It will take time because you must persuade people to buy new television sets, and program makers to re-equip their studios. This is not a cheap thing to do. It is going to be a slow road, but because of history it is bound to happen. Technology does not go backward or standstill.

What do you do now?

I still work for the EBU, but just as a Consultant to the EBU Technology and Innovation Department, which is overseen by the EBU Technical Committee. This is a body of members elected from broadcasters of Europe, including Galina Fedorova from RTR.

What would you say is the peak of your professional career, your main achievement?

I was lucky to be in the right places at the right time. I think, since everything goes back to Recommendation 601, the first digital television standard, it would be that. However, all of them were great fun and enjoyable times.

Tell us a bit more about your family.

I have a brother who was a journalist in Wales and is retired now. I am also married; I met my wife at Southampton University where she studied classical languages. She is a teacher, and she taught until she retired a few years ago. We have three children. My son Peter works for the BBC, in television news and engineering. He followed me: he went to the same university and studied electronics there and is now with the BBC. My daughter is a macro-economist, and my other son is a web developer. I am very proud of all my children.