Interview with Umid Malikov, Uzbek director and cinematographer.

— When and where were you born, who are your ancestors, what kind of family do you come from?

I was born in 1985, in Tashkent. I come from a creative family. My mother and father are musicians. My mother is a pianist and taught at the conservatory. My father is a cellist. They are now retired.

I am a cinematographer, I worked at the Uzbekfilm studio. The studio became part of a film concern, and it turned out that all creative workers work on a contractual basis. I am a freelancer and a lecturer at the “Focus” film school, at VGIK, and at the Institute of Arts.

I mainly teach. There is work in cinema, but not as much as I would like. I have to engage in scientific research, the main thing is not to waste time. Currently, I am a doctoral candidate, God willing, I will defend my thesis. The topic is dedicated to metaphors, to be more precise, “Metaphors as a Leading Factor in Visual Solutions in Uzbek Cinema.” Many directors forget about metaphors, and the audience has stopped reading them. This is the problem, the loss in visual solutions. As a cinematographer, working on projects, I often think about this and suggest it to directors, but it turns out as it turns out…

— Why didn’t you follow in your parents’ footsteps?

There is a saying that talent rests on children. I did not try to enter music school, and my parents did not want to make a musician out of me either.

But my grandfather loved photography, he was a radio operator. He had his own darkroom, and I was very interested. I didn’t understand the process of printing photographs, but it fascinated me. Then I began to develop and realized that there is such a field as cinematography.

— At what age did you first pick up a camera?

At five years old. I took the camera from my grandfather and tried to photograph something. Naturally, nothing worked out, I had to set the exposure correctly. My grandfather gave me a FED camera, he had a Zenit.

And I broke it, the camera stopped working, then I repaired it and worried. And little by little, I started working. There was a book, “Learning to Photograph,” a small Soviet brochure. It described the Smena camera. It was interesting to me.

I didn’t enter the institute right away. I really wanted to follow in my grandfather’s footsteps, to go to the communications institute, to the radio engineering direction. I prepared for it, but it didn’t work out. My mother said there was a theater institute, either directing or acting. And my friend’s father worked at the Uzbekfilm studio as a production manager. One day, my friend showed me photos and said he was studying cinematography at the institute. Now he works at the “Mir” TV channel. I decided that I would also apply to the theater institute for cinematography. I entered on a budget basis. I believe I was very lucky with my profession choice. I got into the workshop of an amazing master and a wonderful person, Turdy Nadyrovich Nadyrov, a documentary cinematographer. And I started studying. Then I went on to a master’s program with cinematographer Fayziev Khatam Khalmatovich.

— Do you remember the darkroom from your childhood?

Yes, of course. There was an ordinary Soviet enlarger, “Youth” I think. Red light, image development. Now I understand that it’s chemistry, but as a child, it was very captivating. Plus, my grandfather did retouching by hand, sealing something there. Everything was done by hand: the timer, exposure time, developing the films, drying. A completely different world.

I teach at the institute, and cinematography students print photographs from a printer or a machine, and they don’t understand the process. When I was studying, there was still film. I developed photographs myself in the basement of the photo lab, and the attitude towards all of this was a bit different.

Classical photography is now gone. If everyone had the opportunity to touch it, at least there would be an understanding of how film works. Now everything is averaged, whether in Russia, Kazakhstan, America, or Europe – everyone shoots with digital cameras.

A cinematographer’s arsenal still includes composition, light, and internal feelings, which are not easy to describe. But the process that can be called magic, what the image will be and what will come out, that’s not there. There are pros and cons.

I worked as a second operator on film, and exposure correction was a big responsibility. I am glad that I experienced this period and know a little about this process.

— When you were in school, were you exploited as a photographer?

No, you know, I wasn’t exploited as a photographer because we had a photographer who came for money. It was a statistical school in a residential area of Tashkent. Two of my classmates’ fathers died in Afghanistan. It was not a school for the privileged.

It was about survival in school. Survival and a tough school. I did judo, played sports; there was no concept of creativity in school. Even now, my classmates don’t understand how I became a cinematographer.

— Why did you choose judo?

There was a judo section in the school and a youth sports school for judo. Many wrestlers came from this area.

— How did you do in school?

I was a C student. I knew Russian. But I didn’t like to read. The teacher gave me failing grades, and we resolved it by either providing a lamp or three liters of gasoline. I would unscrew a light bulb from the next classroom.

— Did you study for 11 years or 10?

Nine classes. And I ran away from school because I was categorically tired of it. I went to a radio technical college.

— Why did you choose radio technology?

My grandfather was a radio operator. I saw the process, how he soldered and repaired equipment.

— In which specialty?

RRT — short for radio communication, broadcasting, and television. Master of radio electronic equipment.

— After ninth grade, did you study for three years or four?

Three years in a vocational college. In Soviet times, it was called a vocational technical school. There I gained knowledge and a profession, working as a master of radio technical equipment.

— How did you study in college?

I studied excellently. In school, my ability to negotiate with teachers helped me because I knew when to greet them properly, do an extra paper, or an additional outline. Everyone has to go through such a period in life. The East is a delicate matter. You need to know how to negotiate.

— When did you earn your first money? At what age?

In the 2000s, I started working in a workshop. I repaired TVs, tape recorders, amplifiers. Technology was just beginning to gain momentum; in any profession, you need to learn and improve your skills. So, little by little, I earned money.

At that time, it was fashionable either to be a military man or a businessman. I wanted to enter the military, but it was unrealistic. You needed connections. I didn’t get in, but I managed to get a job, not officially, but as a photographer. The first time I took a camera was there. I had to photograph criminal incidents… There was no romance in it. I worked for less than a month. I remember my mother looking at me and saying, “Stop this job.”

I earned very well. But still, because of the job, a person changes, and parents see that the child’s eyes are changing and realize that life is completely different, so I left.

I started preparing for the theater institute to become a cinematographer.

— At that time, you were 19 years old, weren’t you drafted into the army?

I brought a certificate to the military registration office that I was preparing for the institute. Then I brought a certificate that I was a student. Later, I entered the master’s program, and time flew by.

— Did you enjoy studying?

Yes, in the institute, of course, it’s a completely different atmosphere, a completely different world: creative people, trips to the theater, exhibitions, movie premieres. Naturally, my circle of communication changed completely.

After graduating from the radio technical college, we had an annual reunion with my classmates. I realized there was nothing to talk about; I was just wasting my time. No offense, but I think my mindset changed.

— How did you get into cinematography?

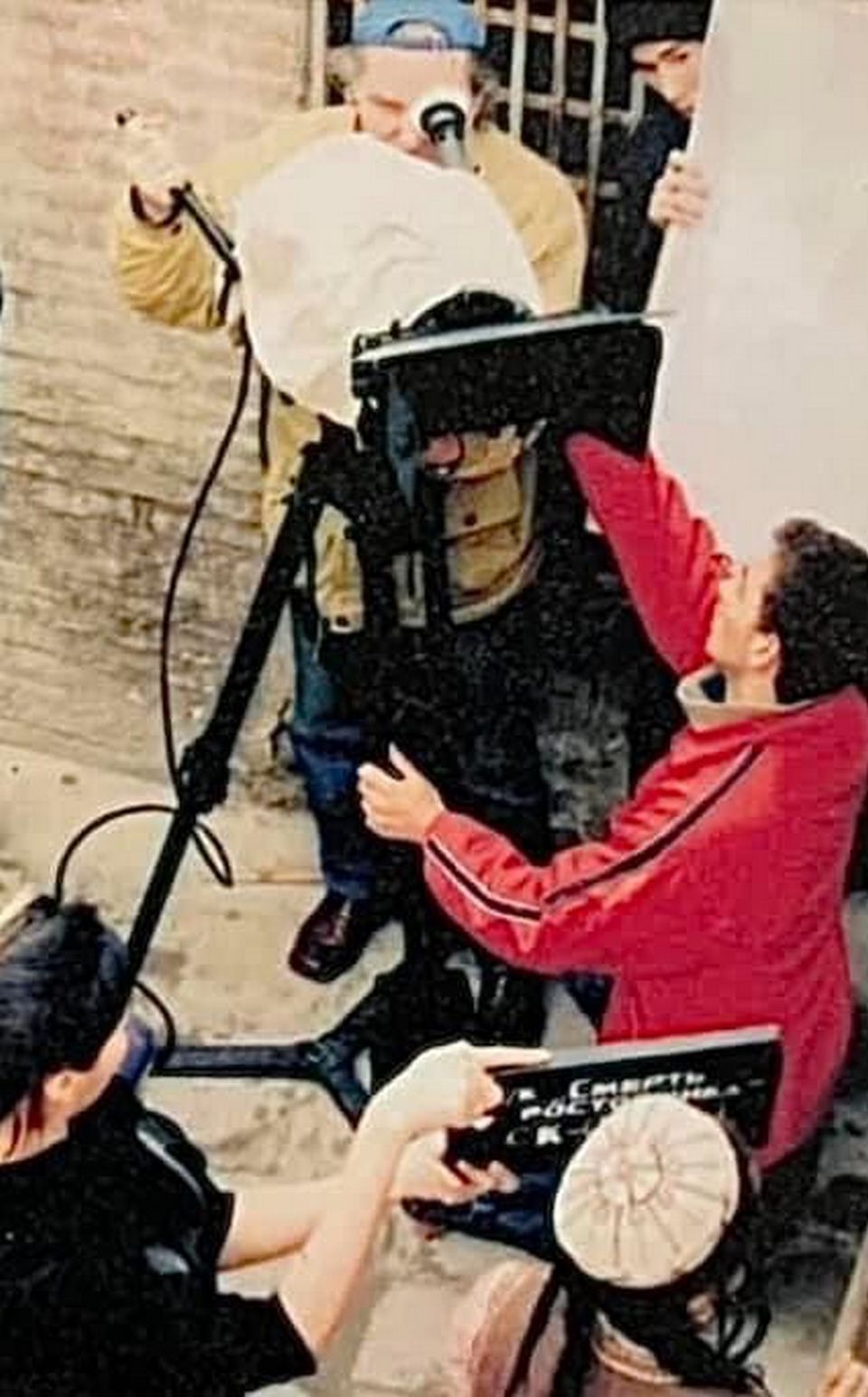

I started learning, photographing, studying frame composition, but like all students, I lacked practical experience. There was a project on ORT called “The Golden Calf.” Oleg Menshikov played the lead role, if you remember. I don’t recall who the director was. I participated in that project, working as a lighting technician. Part of the series was filmed in Bukhara in September, but it was still hot during the day, around +40 degrees. I earned my first 400 dollars there in two weeks. And I saw with the corner of my eye how much the cinematographer earned, plus several zeros.

You know, that was motivation. The desire to earn money arose immediately. I understood that this profession required knowledge of composition, understanding frames, and working with light.

So I began to study the filmmaking process even more diligently, attending the institute and bombarding my teachers with questions about the filmmaking process since films were only shot on film.

— How did you get into lighting?

The “Bayram” film studio, which is very famous, still operates in Uzbekistan. They were hiring lighting technicians for a project, and at that time, my classmate, the late Ruslan Yarulin, was working there. By the way, Bakhadir Yuldashev, who is also now a great cinematographer, worked with us.

They invited me to join the project as an assistant. I gladly agreed. That’s how I ended up in the lighting crew.

It was my first experience as a lighting technician. I understood the internal structure, how the group works. I didn’t continue as a lighting technician after that; during my student years, I felt it was necessary to go through this school, especially on a good project, rather than just carrying equipment and helping without a clear purpose. And here was such a good project, so it was interesting.

— How did you start working as a cinematographer, assistant cameraman, or second cameraman?

Later, I went to the “Uzbekfilm” studio during the holidays, said I worked on a Russian project as a lighting technician and wanted to be an assistant. They said there were no openings for assistant cameramen, everything was occupied, so they offered me a photographer position. I combined the roles, photographing the backstage, the process, and helping the cameraman. Eventually, I became a cameraman’s assistant.

— This was parallel to your studies, right?

Yes, yes, all during my studies. Eventually, I stopped attending the institute. My ability to negotiate helped me.

— How did you manage to negotiate with your mentor?

I only attended my mentor’s classes, but I didn’t go to general education subjects at all. You couldn’t negotiate with the mentor. The conversation was always brief because my mentors were very self-sufficient. Turdy Nadyrov was the chairman of the union of cinematographers; you couldn’t fool him. And my mentor in the master’s program, Khatam Fayziev, never compromised his principles, not even on Teacher’s Day, and never accepted gifts.

These were the kind of mentors I had: strict, fair, with a Soviet mindset. In this regard, I was very lucky with my mentors.

Much depends on the mentor. A true student absorbs everything like a sponge, from interactions with colleagues to certain details in the frame. I often recall my mentors, especially during the teaching process.

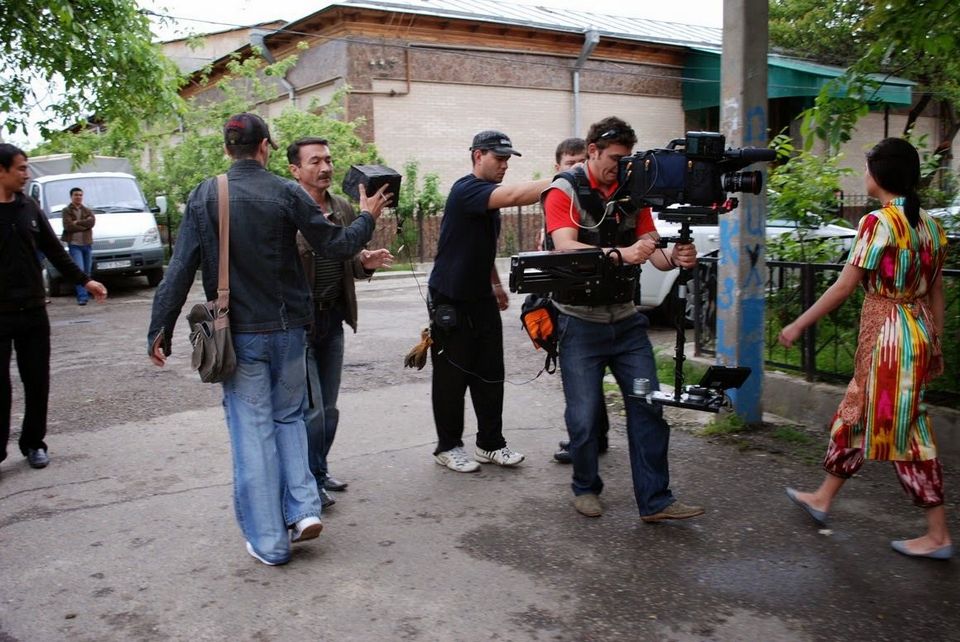

At the Uzbekfilm studio, I started working as a second cameraman and Steadicam operator. I acquired Steadicam skills from the talented cinematographer and my friend Ivan Pomorin on the film project “On the Edge” directed by Rauf Kubaev, with Archil Akhvelidianni as the cinematographer. Ivan Pomorin now has a film company in Moscow called “KinoGorynych.”

I understood that I needed to move forward. You could work as a focus puller and Steadicam operator for a long time, but getting the first main role as a cinematographer was fantastically difficult. There were many cinematographers, but few films at that time.

I had to shoot my thesis project, and I was lucky. I was offered to shoot a 12-episode TV series at Uzbektelefilm and submit the project as my thesis, with the condition that there would be no fee or salary.

I immediately agreed. At that time, the fee was not important to me; I needed to make a name for myself. As a result, I defended my thesis, received a diploma with a full-fledged project that aired on television with government support. The most famous and commercially successful film director, Bahrom Yakubov, saw my cinematography work. We formed a creative tandem. We worked together for many years and made good films.

— The director of the series was a brave person to take a final-year student as the main cinematographer. How did he decide on this?

The director was my teacher in the history of world cinema. By the way, he is now my scientific advisor. In my creative journey, it so happened that I shot my first project and thesis with Aybek Kapadze. And now he has become my scientific advisor in my doctoral studies, as they say, the stars aligned.

The teacher saw that I was shooting, that I had some skills, and he, as a director, trusted me.

He saw potential and gave creative freedom to implement the project.

— How many episodes were there?

12 episodes. We went to the Fergana Valley three times each season. The trips were for 20 days, we stayed there. Each shift was 12 hours. That was the project.

— So three times a year or just three times?

Three times a year, for 20 days each. 60 shooting days. That was how it was filmed at that time, and everything was fine. Now, my friends, who are producers, have their own companies. They shoot one episode of 45 minutes a day. There’s no room for creativity there; it’s just routine, and the main goal is to meet the runtime.

— What did those 12 episodes and working with that director give you?

When doing coursework, there’s a certain freedom. But in production, you’re given 2-3 hours to finish an object: prepare in advance and shoot. This gives a cinematographer a backbone; you understand that time is limited, your budget is not flexible, and in this regard, it helped me.

At that time, a law on state support for TV series was passed in Uzbekistan. The press and TV shows were talking about the series, and Bahrom Yakubov, a director who was making commercial films at a private studio, saw it. His films attracted all the youth. A film with a budget of $60,000 would pay off 9-10 times. The whole country still watches these films. Private cinema was at its peak then. I was very lucky to work with such a director.

We had Rustam Sagdiyev, who is still alive and well, working, and Bahrom Yakubov. They were the two directors who caught the wave, the youth trend, and brought people to the cinema.

The series was a great springboard.

— How many projects did you work on with them?

I shot more than ten films with Bahrom Yakubov.

— How did you transition to digital?

I worked as a second cameraman on film; I didn’t shoot as a director of photography on film. With film, the dynamic range is larger, and we worked with directed light.

I tried to do the same in the series, but I saw that the dynamic range was completely different, and it turned out too bright. I realized that I needed to soften it. Gradually, by making these mistakes in the series and reviewing the footage, I drew conclusions.

The series helped me understand the digital camera. It was the DigitalBT.Cam, the coolest digital camera at the time. I understood the capabilities of this camera, and everything started to work out.

— Your first education was technical. How much did you apply that knowledge?

In the theater institute, physics was in the first year for cinematographers. I immediately got top grades, and the teacher said, “You don’t have to attend because you know everything.” The section on electrical engineering, waves, calculating resistance, the power of devices, how many kilowatts, which cinematographers need to know in advance. I understood this even before becoming a cinematographer. In this regard, basic school knowledge of physics and technical knowledge helped a lot.

— Did you apply any ideas or invent something on the set?

I mainly rely on the creative side and don’t invent any know-how. Cinema, director, script, dramaturgy. The viewer must understand what the director wants to show. This is important to me. Many cinematographers create beautiful shots, making the image stunning, with sunset lighting, etc. But for me, beauty should also be in the script. If it’s written beautifully, I’ll shoot beautifully. If something bad is written, I’ll shoot accordingly.

I had an experience with a well-known singer, I won’t name her, shooting a film. She asked if we could place the light here, as she’s filmed in music videos, and she looks good. But in the script, she was a cancer patient with a week to live. I said, you know, this music video approach won’t work here. There’s a story we’re telling for the viewer. We worked not for the frame but for the story. If the script or episode requires beauty, then I’ll shoot beautifully.

— How did teaching come into your life?

In the master’s program, there are teaching hours during the studies that need to be delivered to undergraduate students, so I started giving lectures.

The topic of my diploma was “Comparative Analysis of Digital Video Cameras.” At that time, Panasonic, Sony, Canon, Red One came out. I shot a film on Red One, which was the first in Uzbekistan, and analyzed these cameras: their image, dynamic range. I conducted simple tests and described everything. My diploma work was technical. Now, after working in cinema, I realize that technology is just a tool that needs to be used skillfully.

Metaphor and deep understanding of the story are much more important than technical aspects. Now, when even an iPhone shoots in 4K and artificial intelligence replaces cinematographers, screenwriters, and artists, and technologies continue to develop, even resurrecting dead actors for filming, creating films requires special attention to metaphors and imagery.

— When and what did you start teaching?

In 2009, at the Institute of Arts, a course was left without a mentor. The head of the department offered it to me. I was hesitant. Although I was making films and had some experience. I worked there for a year, but due to a heavy workload, filming, and trips, I had to leave the job at the university.

Later, a private film school “Focus” opened. Creative, depoliticized. There I started teaching a cinematography course. Three stages of three months each, starting with the basics of photography. We went on international meetings with the school. And I realized – when there is a topic, when there is an audience, you can talk about something.

In 2021, a VGIK branch opened in Tashkent. At the branch, I teach film composition, film lighting, and introductory lectures on cinematography for producers and directors.

Since 2023, I have also returned to the Institute of Arts, giving lectures on film composition and film lighting.

Taking a course entirely is a big responsibility. To get results, you need to work with students for a long time, dedicating yourself. We are responsible for those we tame.

— What do you consider your main achievement in your professional activity?

Honestly, I haven’t even thought about it. Because I believe that achievements are still ahead. Whatever it is, you need to keep filming. In Uzbekistan, my colleagues in the field and students know me; I have many students.

I visit many cities in Uzbekistan; we have 12 regions and one autonomous Republic. Many people who film or work in the field of cinema know me.

Yes, maybe some say that Uzbek cinema is local, that you need to conquer Hollywood. I wish these people luck. Our cinema may be local, but I think it is unique and very interesting.

In Uzbekistan, people are very friendly. I have friends everywhere; my profession helps me in this regard, meeting people, making new acquaintances in different fields.

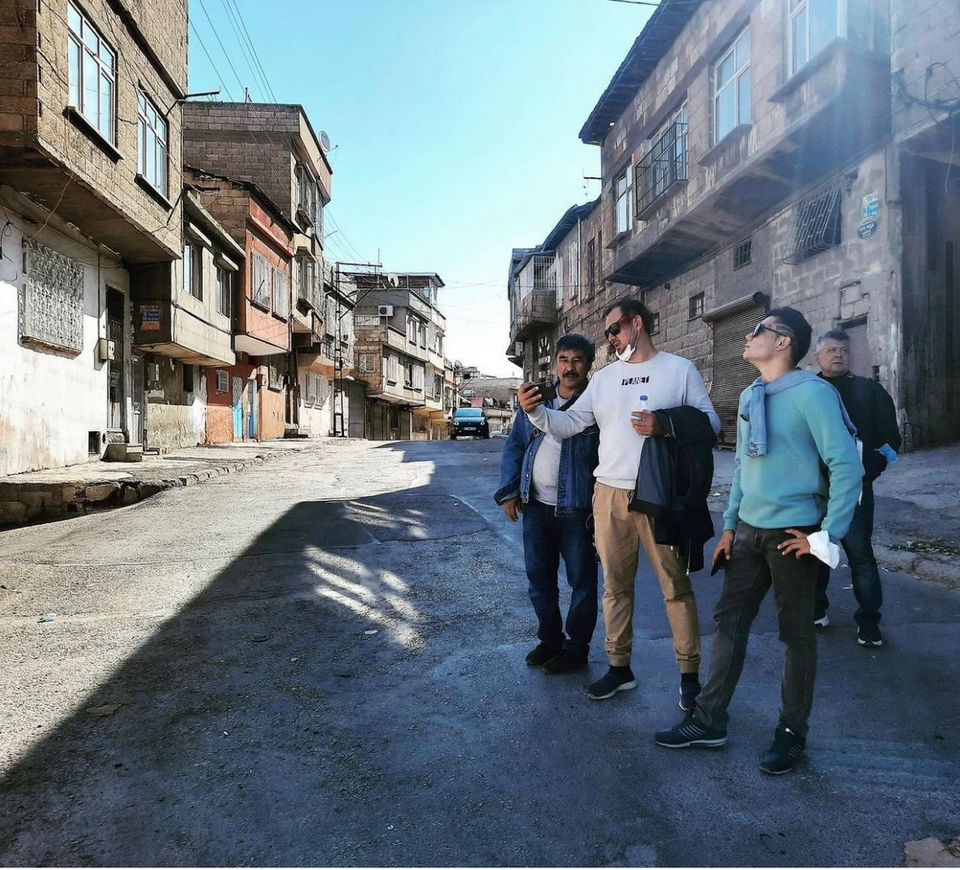

Recently, I’ve also been working as a director, creating documentary projects about people. Businessmen, leaders of large corporations, creative people, people with unusual professions, true Uzbeks who work for the benefit of their country, region, and family.

I recently made a film about the Uzbek mahalla, how this system works. Mahalla is a neighborhood, a city system within a city.

These are the kinds of films that tell a little about Uzbekistan and its people, kind and depoliticized.

— Is “Mahalla” festival cinema?

Yes, every year there is a film festival of Turkic peoples in Turkey called “Korkut Ata.” I prepared a film for this festival this year, and I hope we will take it and show it.

— How has life unfolded on the other side of the lens, outside of work?

Thank God, everything is fine. I have a wonderful wife, three children, everything is good.

— Where did you meet your wife?

At the theater institute. She is an actress, now studying for her master’s, acting.

— What are your children’s inclinations?

One is a footballer, inclined towards languages.

— What does cinema mean to you?

For me, cinema is life, the reflection of destinies and stories on the screen, which the viewer watches and lives through.

I believe that everyone should have their own cinema, unique. That’s what makes it different. Indian cinema, Iranian, Russian – every nation should have its unique cinema. Cinema unites people and reflects their traditions and values. Each country and nationality should have its own cinema so that we can see it, rejoice, and congratulate filmmakers on their creative successes.

Wishing everyone creative flights!